- Home

- white paper

- Well-Being

Sound Therapy is a listening program that uses music programmed with algorithms found to have a profound and calming effect on the emotions and the nervous system.

When we experience trauma, habitual negative thought patterns are established which then cause alteration of the neuronal pathways in the brain. Research has proven that these pathways can be changed when certain brain centres are stimulated. Stored emotions and associated repetitive thoughts can be released if the neuronal firing patterns associated with them are changed.

Research has established that:

- Stressful experiences can be locked into the auditory system (Skoe and Chandrasekaran, 2014).

- Auditory memories can trigger reactions in the limbic system (Lutz, 2008).

- Remapping brain pathways changes emotional experience (Klimecki et al, 2013).

- Left brain stimulation helps to lift depression (Davidson, 1992).

- Activating the vagus nerve means that benefits similar to meditation can be achieved through Sound Therapy.

Stressful experiences can be locked into the auditory system

Just as emotional memories can be stored in muscle tissue, memories can also be locked away in our auditory system, according to Dr Tomatis, one of the first researchers to investigate the auditory environment of the foetus. Tomatis’s theory was that the auditory relationship between baby and mother lays the foundation for all our other relationships and is therefore the crucial point of intervention to bring about change in the person's psychological response to sound and language. The resolution of such memories is achieved through a reopening of the auditory system (Tomatis, 1991).

Other research has confirmed these premises (Skoe and Chandrasekaran, 2014). Studies have found that brain damage prevents the healing of emotional memories (LeDoux, 1989). Yet healing of suppressed traumatic memories can occur when they are able to be processed through the sensory system.

“Repressed traumatic memories can often function within an unconscious system of sensory transfers and exchanges, a delicate cognitive cryptography that, in transforming atrocious details into beautiful fragments, can also transform the traumatic event from an experience that destroys us into one that reconstitutes us, heightens our sensory awareness of the world, and makes us who we are (Silent Jane, 2010).

Results of a study which appeared in the journal of the Association for Psychological Science in 2008 indicated that the brain uses more efficient mechanisms in auditory memory than in visual memory. This infers that the human brain appears to be a keener detector of auditory change than visual change (Demany, 2008).

Auditory researchers agree that experience stored in auditory memory is very profound and important for our emotional wellbeing. “You get the comfort hormone prolactin when you use music,” Levitin says. “That's the same hormone that is released when mothers nurse their babies. It's soothing.”

Conversely, negative emotional states involve links between the auditory system and multiple brain centres concerned with negative emotions. “Pathophysiological processes underlying psychiatric disorders such as depression, obsessive compulsive disorder and schizophrenia involve the basal ganglia and the connections to many other structures, particularly to the prefrontal cortex and the limbic system” (Stathis, 2007).

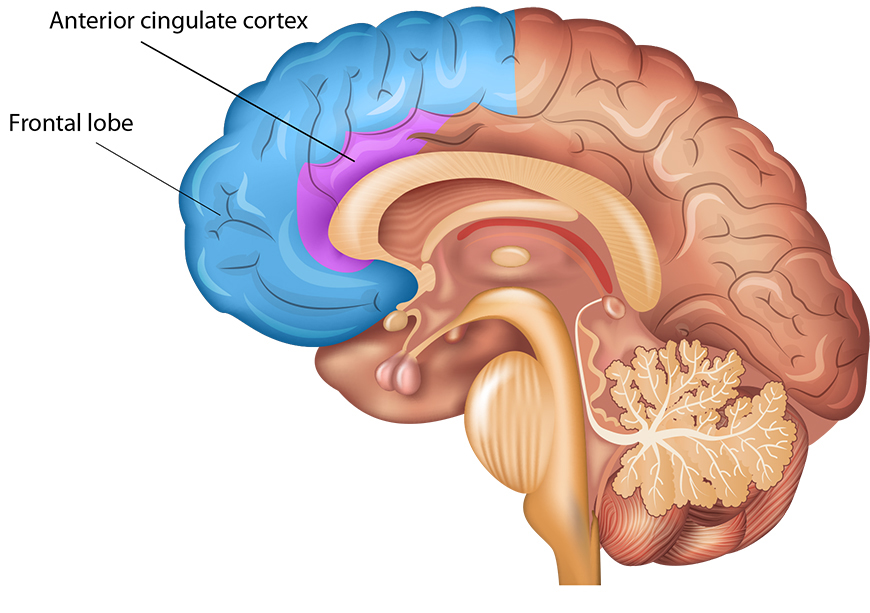

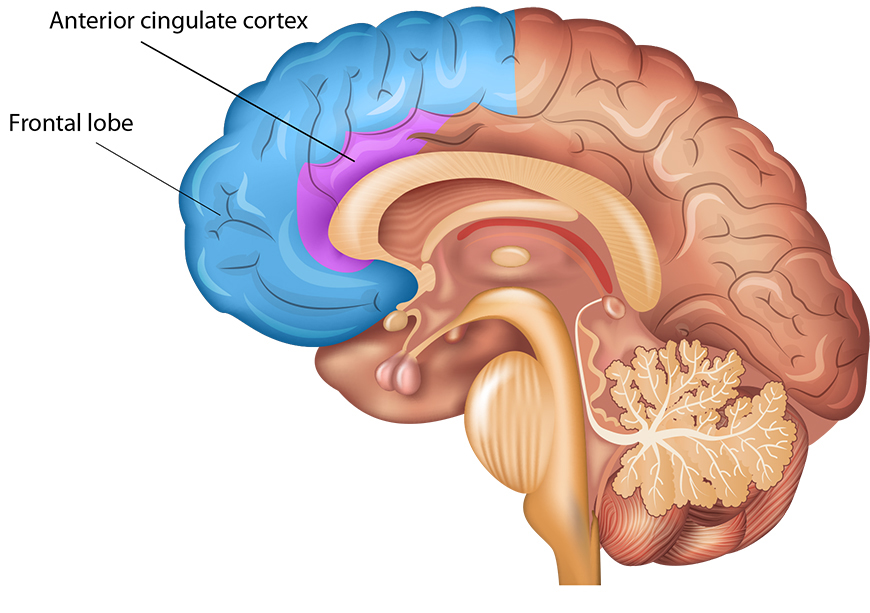

The anterior cingulate cortex and attention

One structure of particular relevance to our mental state is the anterior cingulate cortex, a small asymmetrical part of the prefrontal cortex. The prefrontal cortex, just behind the forehead, is where we feel that our sense of identity and existence is positioned. The anterior cingulate cortex is the brain’s emotional control centre, and is relevant to our moods as it gives us our ability to focus our attention internally on our own thoughts.

In depression, external stimuli become relatively meaningless compared to internal preoccupations.

Such repetitive negative thinking is thought to be linked to this structure (Carter, 2002). The brain of a depressed person lacks outside focus, as the areas used for directing the attention to the outer world are deadened.

The anterior cingulate cortex lights up when we concentrate, particularly on things that are generated inside ourselves, like pain, and is hyperactive in mania.

Some studies have identified the anterior cingulate cortex as the part of the brain most activated by social rejection and the emotional pain this creates (Posner 1994, Lieberman 2003). Posner’s theory is that in negative emotional states, a vicious cycle is formed between the amygdala, the prefrontal lobe and the anterior cingulate cortex.

Remapping brain pathways changes emotional experience

Tomatis, an ear doctor with a special interest in embryology, observed that the development of the brain is intimately integrated with the development of the ear. It is through auditory linguistic stimulus (hearing the mother’s voice while still in the womb), he posited, that the foetus forms large numbers of brain pathways. Rather than the brain developing first, and language subsequently being learned, brain structure is created as a result of language exposure. In fact, much of the brain itself grows out of embryonic ear tissue. Therefore, Tomatis says, the brain is a differentiated ear, rather than the other way around (Tomatis, 1991). No wonder sound affects us so deeply!

Research has shown that “music can lift the spirit and rewire the brain” (Holden, 2001) and provided evidence that music can be used to remap brain pathways. “The cerebellar of male musicians they found were 5% larger than those of male non-musicians” (Holden, 2001).

Auditory physiologist Hubert Dinse at Ruhr University in Buchum, Germany stated, “Processing of music is much more distributed than one would expect from simple anatomy,” (Holden, 2001).

Because of the way it stimulates a variety of different brain centres, music has profoundly beneficial effects on mood and state of mind. Blood and Zatorre found that in response to the pleasurable effects of music, “Cerebral bloodflow increases and decreases were observed in brain regions thought to be involved in reward/motivation, emotion, and arousal, including central straitum, midbrain, amygdala, orbito-frontal cortex, and ventral medial prefrontal cortex” (Blood, 2001).

These linkages are a clue to the way that sound so profoundly effects the functioning of our entire nervous system and emotional responses, helping to resolve chronic grief, anger, depression and more, as numerous studies have shown.

“Findings indicated that music therapy was more effective in decreasing state anxiety than was an uninterrupted rest period” (Wong, 2001).

“Studies, as well as clinical experience, have shown that musical intervention has been helpful in assisting patients with pain management in a variety of medical settings” (Presner, 2001).

“A single music therapy session was found to be effective in decreasing anxiety and promoting relaxation. Subjects to receive music therapy reported significantly less anxiety (...) than those subjects in the control group. Heart rate and respiratory rate decreased over time” (Hinjosa, 1995).

Left brain stimulation helps to lift depression

The long-term practice of meditation allows a person to turn off areas of the brain that normally seek stimuli. Researchers also found an observable increase in certain areas in the left brain associated with positive emotions and a sense of wellbeing, peace and fulfilment (Davidson, 1992).

Sound Therapy specifically targets the left pre-frontal cortex and stimulates under-active brain areas by increasing the energy in the neurons, which in turn, it is thought, raises the level of excitatory neurotransmitters. The increased cortical activity, it is surmised, allows the person to practice more balanced and wholistic thinking, inhibits negative recurring thoughts associated with the limbic system and results in more controlled and focused behaviour (Joudry, 2009).

Similar benefits to meditation can occur through Sound Therapy

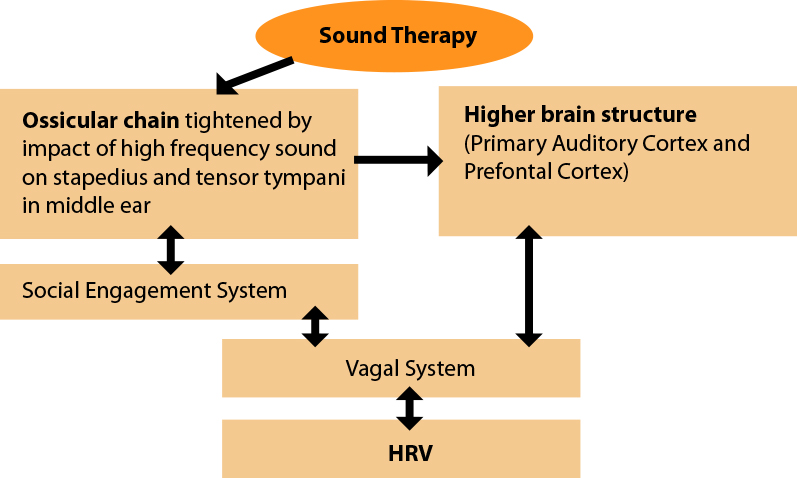

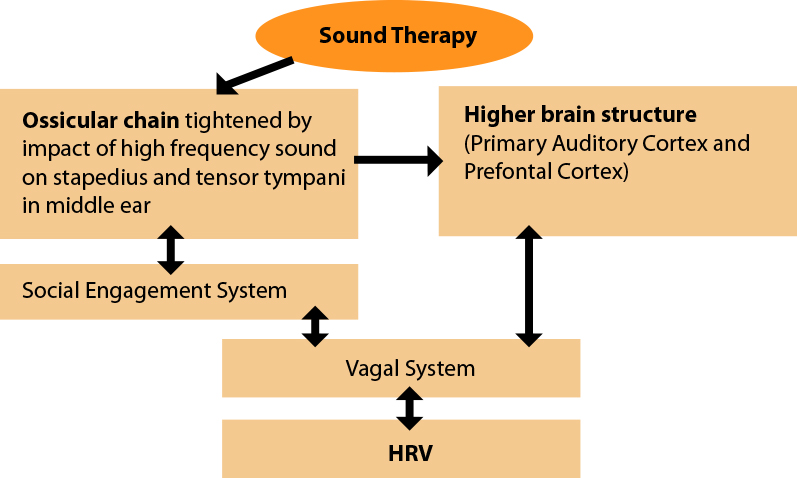

Stephen Porges (2003) has shown that two distinct branches of the vagus nerve are responsible for our fight or flight response and our social engagement response. The vagus nerve affects the function of the middle ear muscles, which play a role in dampening low frequency sound and enabling us to focus on the human voice (Porges, 2011). This leads us to the understanding that stimulation with high frequency sounds enhances the ability of the cranial nerves to act on the middle ear muscles, enabling them to block out low frequencies.

This process also reduces stress and enhances communication and emotional adaptability. This in turn, calms thoughts and feelings, through both behaviour and physiology.

Therefore, improvement in vagal regulation enhances communication and emotional adaptability (Warhurst, 2012).

Figure 1. Model showing possible pathway between sound therapy and HRV. This model (Warhurst, 2012) is a variation on the environment-brain-viscera feedback system underlying the social engagement system.

As an alternative to pharmacological drugs, stimulation of the nervous system is now being considered for treatment of mood disorders. Increased firing of signals in the brain, induced by music, can make a big difference to moods, as these researchers state: “It is important to emphasise that the altered mood did not result directly from the depletion of the neurotransmitters as much as the result of inadequate firing of those cells in the brain” (Vidal, 2010).

“The results of the study indicate that music may be a cost-effective, risk-free alternative to pharmacological sedation” (Loewy, 2005).

The music of Mozart has been proven particularly beneficial in improving brain states. “Results indicate a positive effect of listening to Mozart”, and it worked whether they like it or not! (Jones, 2006).

The use of particular selections of classical music with added filtration for Sound Therapy ensures such benefits. There is ample evidence that when used appropriately, music can change the physiology on which emotional states are based.

Research has shown that music can alter physiological variables like blood pressure, heart rate, respiration, EEG measurements, body temperature and galvanic skin response. Music influences immune and endocrine function. The existing research literature shows growing knowledge of how music can ameliorate pain, anxiety, nausea, fatigue and depression” (Mysaka, 2000).

The effect of Sound Therapy to increase motivation, coordination and energy is believed to be partly due to an increase in the neurotransmitter dopamine naturally generated by the brain. Dopamine is an essential factor for physical motivation and the ability to get up and go. “I’ve done things in the past year that I had been putting off for ten years” said one Sound Therapy listener.

Sound Therapy has been found to motivate people into more activity and overcome depression, so it is possible that it helps to stimulate dopamine production (Joudry, 2009).

More than any other neurotransmitter, serotonin dysfunction has been implicated in depression. When we look at the effects of serotonin it looks a lot like a list of the reported benefits of Sound Therapy. An increase of good feelings, serenity and optimism are frequently reported by our listeners (Joudry, 2009).

One of our Sound Therapy listeners remarked, “I feel a new joy in living.”

Conclusion

Sound Therapy uses specially filtered music to help restore positive emotional function. Tomatis posited that stressful experiences which have been locked into the auditory memories may be released through the neural remapping, and subsequent research has supported this concept. By remapping the brain, Sound Therapy is thought to impact certain areas of the limbic system in order to calm and resolve negative emotions. Focused high frequency stimulation of the left cortex appears to assist in the generation of positive emotions, creating similar benefits to those of meditation. The results experienced by Sound Therapy listeners confirm that the program can have a profound effect on enhancing emotional experience.

References

- Blood, A.J. and Zatorre, R.J., (2001). “Intensely Pleasurable Responses to Music correlate with Activity in Brain Regions Implicated in Reward and Emotion,” PNAS, vol. 98 no 20.

- Carter, R. (2002). Mapping the Mind, London: Phoenix.

- Davidson, R., (1992). “Anterior Cerebral Asymmetry and the Nature of Emotion,” Brain and Cognition, Volume 20, Issue 1 pp 125-151.

- Demany L, et al, (2008). “Auditory change detection: simple sounds are not memorized better than complex sounds.” Psychol Sci. 19(1):85–91.

- Hinojosa, R. J., (1995). “A Research Critique Intraoperative Music Therapy: Effects on Anxiety, Blood Pressure,” Plastic Surgical Nursing. 15 (4): 228-232.

- Holden, C., (2001). “ How the Brain Understands Music” Science 292 (5517), 623.

- Jones, (2006). The Mozart Effect: Arousal, Preference, and spatial performance. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity & the Arts. (1):26-32.

- Joudry, P. and Joudry, R., (2009). Sound Therapy: Music to Recharge Your Brain, Sound Therapy International, NSW, Australia.

- Klimecki OM, Leiberg S, Lamm C, Singer T. (2012) Functional neural plasticity and associated changes in positive affect after compassion training. Cereb Cortex. 2013 Jul;23(7):1552-61. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs142. Epub 2012 Jun 1. PMID: 22661409.

- LeDoux, J. E., Romanski, L., Xagoraris, A., (1989). “Indelibility of Subcortical Emotional Memories.” Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience Vol. 1, No. 3, Pages 238-243.

- Levitin, D., (2007). This is Your Brain on Music, Plume, New York.

- Lieberman, M, (2003). “Rejection really hurts finds brain study”, New Scientist vol 302, p 290.

- Loewy, J., (2005). “Sleep/Sedation in Children Undergoing EEG Testing: a Comparison of Chloral Hydrate and Music Therapy,” Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing. 20 (5): 323-332.

- Jäncke L. (2008). Music, memory and emotion. Journal of biology, 7(6), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/jbiol82

- Mysaka, A., (2000). “ How Does Music Affect the Human Body?” Tiddsskr Nor Laegeforen. 10;120(10):1182-5.

- Porges, S. (2003). The polyvagal theory: Phylogenetic contributions to social behavior. Physiology & Behavior, 79(3), 503-513.

- Porges, S. (2011). The polyvagal theory: neuropsychological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication and self-regulation

- Posner, M. and R, Marcus E, (eds) Images of Mind, New York, WH Freeman,(1994). cited in Carter.

- Presner, J., (2001). “Music Therapy for Assistance with Pain and Anxiety Management in Burn Treatment,’ Journal of Burn Care and Rehabilitation. 22 (1): 83-88.

- Silent Jane, (n.d.). “Beautiful Fragments of a Traumatic Memory: Synaesthesia, Sesame Street, and Hearing the Colors of an Abusive Past” Transcultural Music Review #10 (2006) ISSN:1697-0101

- Skoe and Chandrasekaran 2014, The layering of auditory experiences in driving experience-dependent subcortical plasticity, Hearing Research, Volume 311, Pages 36-48, ISSN 0378-5955, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2014.01.002.

- Stathis, P., et al, (2007). “Connections of the Basal Ganglia with the Limbic System: Implications for Your Modulation Therapies of Anxiety and Affective Disorders,” Acta Neurochir suppl. 97 (Pt2):575-86.

- Tomatis, A. A., (1991). The Conscious Ear, Station Hill Press, New York.

- Vidal, Victor O. (n.d.). “The Role of Stress in Migraine Headache, Serotonin Dysfunction, and the Initiation of Depression” Retrieved 29 June 2010 from http://www.outcrybookreview.com/Serotonin.htm

- Warhurst, L. (2012) Impact of Sound Therapy on Wellbeing, Cognitive Flexibility and Psychophysiological Measures of Emotion and Mood: A Pilot Study, Sydney University.

- Wong, H., et al (2001). “Affects of Music Therapy on Anxiety in Ventilator Dependent Patients," Heart and Lung: Journal of Acute and Critical Care. 30 (5): 376-387.

Copyright Rafaele Joudry

Sound Therapy International 2010-2025

Start Getting Relief Today

Click here to choose your package