- Home

- Information Sheets

- The science behind Sound Therapy’s impact on tinnitus and Meniere’s syndrome

Tinnitus has proven one of the most difficult conditions to treat, and after many decades of investigation, still does not have a generally accepted medical treatment. This article explores what is known, and looks at new scientific explorations which can add useful and different approaches to treating tinnitus and related ear problems.

We have learned that tinnitus takes place in the brain, but that the ear, and indeed multiple neuro-sensory pathways, play a role in its continuance. Tinnitus can be triggered by a wide range of auditory system injuries. Recent investigations of sensory-based therapies have opened the possibility of remapping the auditory system to bring relief from tinnitus.

One of the most promising is Dr Tomatis’ method of re-integrating the auditory system by rehabilitating the middle ear muscles through active sound stimulation with Sound Therapy. Though it was invented several decades ago, and has built a strong following of therapists in the sensory integration field, the Sound Therapy method has not yet received the full medical recognition it deserves as a viable tinnitus treatment.

CAUSALITY

Science has found that tinnitus occurs in the brain (Jastreboff 1993; Leaver, 2011). While it was previously assumed to be an indication of an ear problem, greater understanding of neural sensory function has deepened our understanding in recent decades. Tinnitus is now known to be an indication of a systemic neural irritation, similar to chronic pain (Rauschecker et al 2015).

PREVALENCE AND TREATMENT

Although tinnitus now affects up to 60 % of the population (Australian Hearing, 2008), 94% of tinnitus patients are routinely told that no treatment is available and they must learn to live with the condition (Holmes and Padgham, 2009). It is not uncommon for a tinnitus sufferer to seek advice from up to 20 clinicians in attempting to find a cure (Jastreboff 1993, Padgham, 2009).

For many decades, masking (covering up the sound with an alternative sound source) was accepted as the only viable way of managing tinnitus. New research on the neurophysiology of tinnitus and the plasticity of the cortex, indicates that tinnitus can be relieved by remapping auditory pathways in the brain (Rauschecker et al 2015).

A summary of the evidence:

- Tinnitus most often begins with auditory system injury (Engineer et al, 2011)

- Tinnitus occurs in the brain (Leaver, 2011)

- Some tinnitus-related ear injuries can be repaired by sound (Engineer et al, 2011)

- Auditory remapping is possible (Thompson, 2011)

- Auditory remapping can reduce tinnitus (Rauschecker, 2010)

- Ear muscle function is related to vertigo (Tomatis, 1991)

Auditory system injury

Introduction

The most common cause of tinnitus is noise damage (Axelsson, and Prasher, 2000). This is an indication of how responsive the ear is to noise, and the fact that noise or sound is the most direct and obvious way to produce changes in the ear and the auditory system.

Continuous exposure to noise above 85dB is known to cause permanent hearing damage (Fausti 1995.) This type of damage is likely to affect the cilia (the hair like receptor cells in the inner ear) and has a flow-on effect on the nerve pathways and cortical centres they supply. Tinnitus can also result from head injury, infections, tumours, viruses and stress. In effect, any damage or injury to the anatomy and physiology of the auditory pathways can result in tinnitus. However, the tinnitus noise itself, or the factor generating the experience of noise, occurs within the brain, as evidenced by incidents where the auditory nerve is severed but the noise continues. (House and Brackmann, 1981) Therefore, it is the brain’s interpretation of sound that has to be altered to relieve tinnitus. (Rauschecker, 2010)

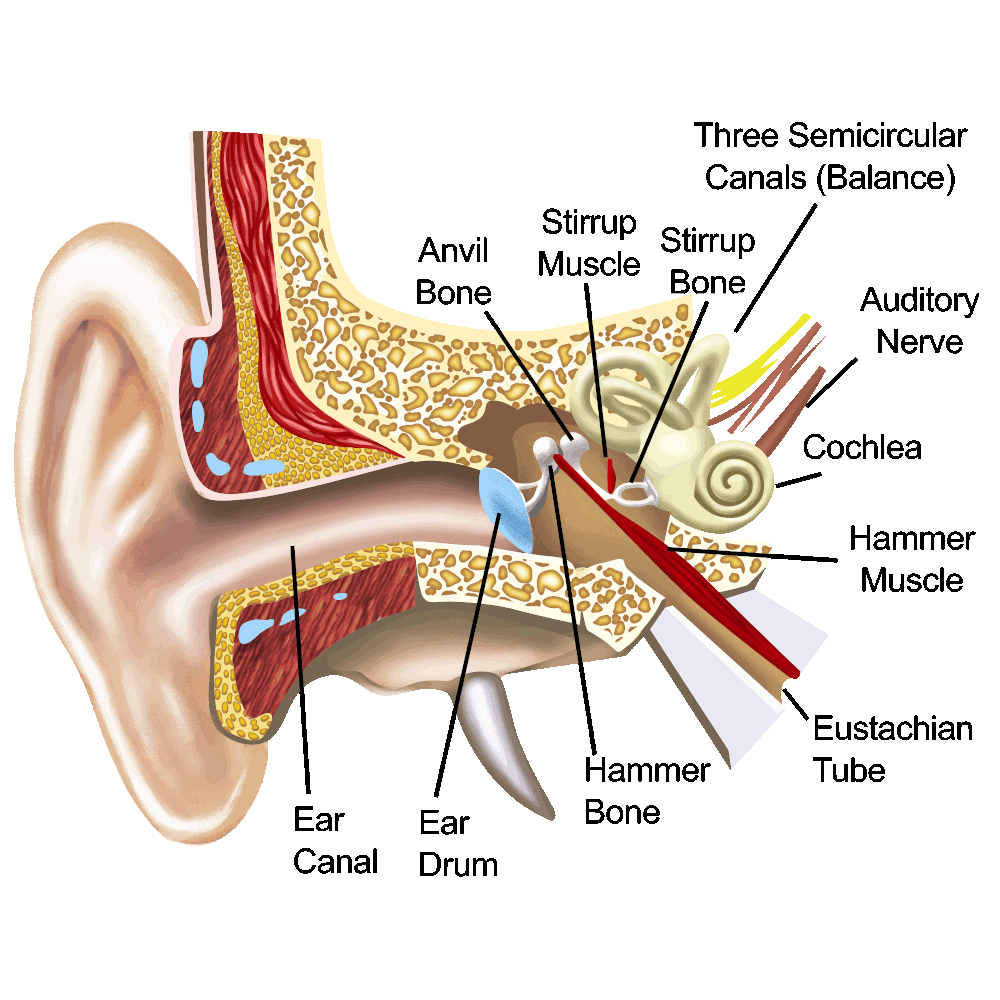

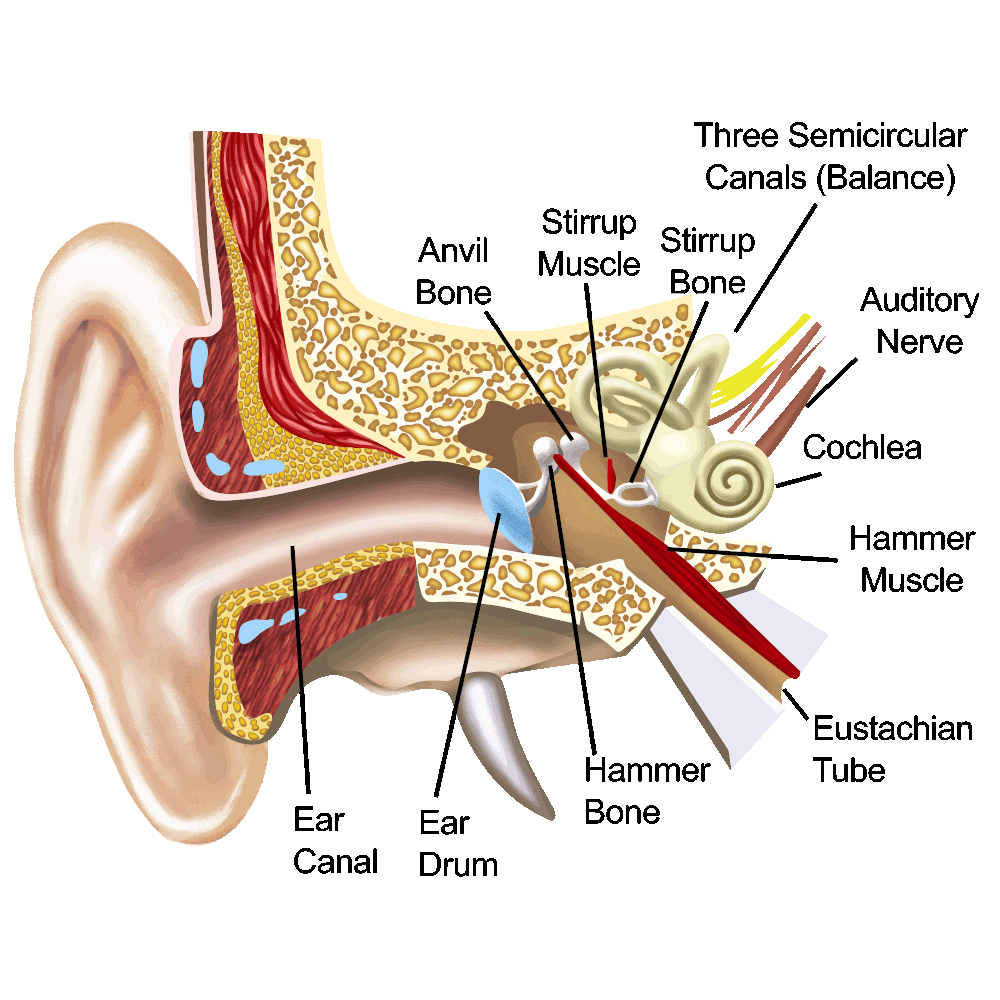

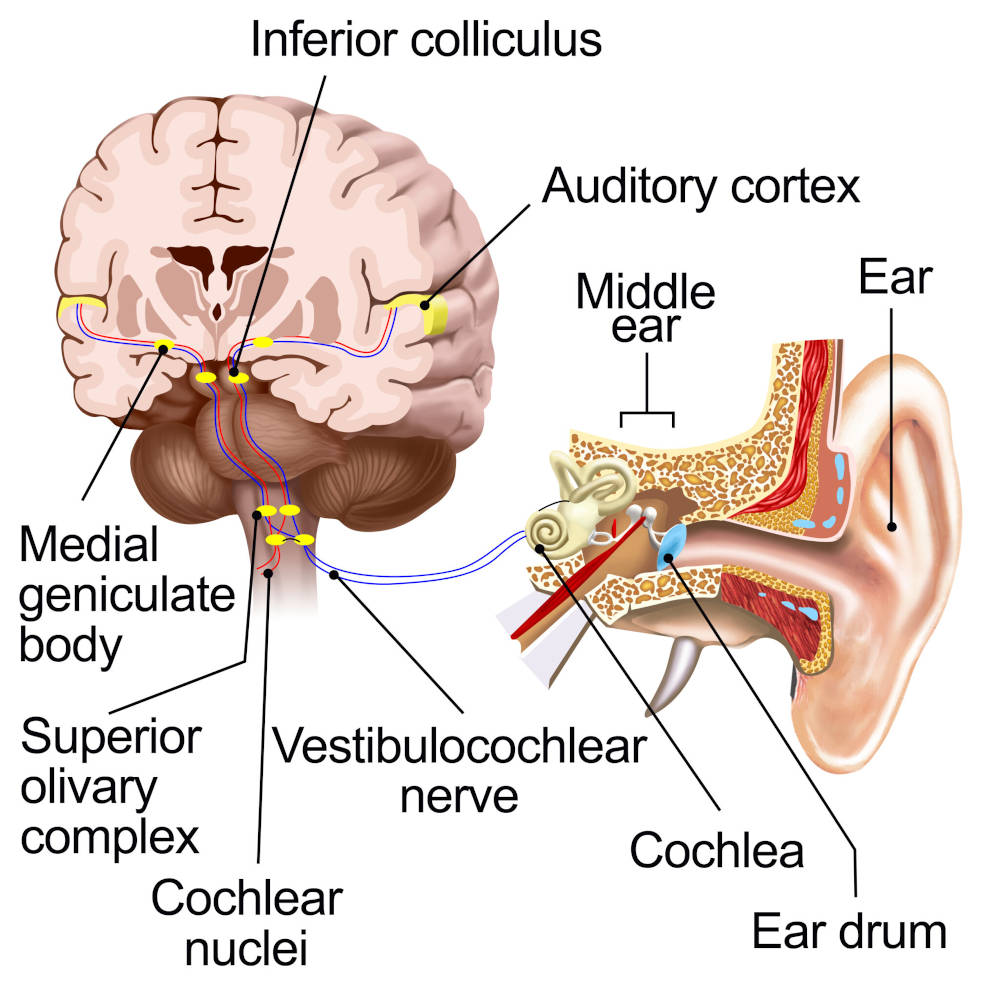

Significance of the ear in our nervous system

The ear has several functions: hearing, pressure sensation, balance, sense of movement and spatial orientation. Its deep and varied integration into our various sensory systems is cause to think more broadly about its purpose. It appears to play a more significant role in our overall functioning than previously thought. In order to better understand how these treatments might work, we need to appreciate that the ear is part of the nervous system. This means that many different aspects of our perception and function are related to the health of the ears. In fact, the ear is linked to ten of the twelve cranial nerves (Figure 1) indicating its impact, through sensory integration, with many aspects of our nervous system (Weeks, 1989).

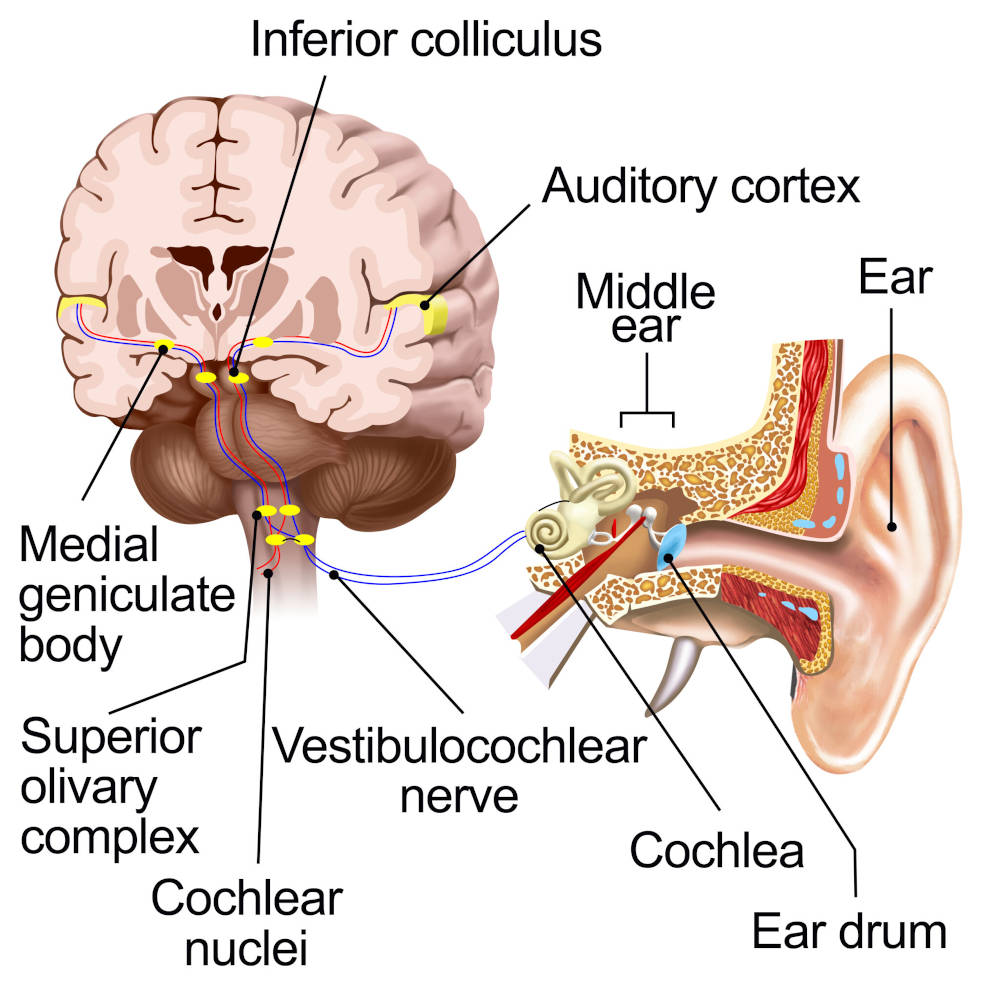

Auditory-neural integration is a two way street, since there are both sensory and motor nerves feeding into the auditory system (Sidlauskas, 2003; Delano and Elgoyhen, 2016). Researchers now recognise that, just as brain plasticity produces problems like tinnitus, it can also be the key to their recovery (Rauschecker 2015).

| No | Nerve | links to ear |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Olfactory | |

| 2 | Optic | auditory nerve |

| 3 | Occulomotor | auditory nerve |

| 4 | Trochlear | auditory nerve |

| 5 | Trigeminal | ear drum |

| 6 | Abducent | auditory nerve |

| 7 | Facial | ear muscles |

| 8 | Auditory | inner ear |

| 9 | Glosso-pharyngeal | oval and round window of cochlea, Eustachian tube and ear drum |

| 10 | Vagus | ear drum, pinna |

| 11 | Spinal accessory | vagus |

| 12 | Hypoglossal |

All of our sensory input is gathered and sorted in the cerebellum, near the brainstem, and then disseminated to various brain centres, to enable us to make sense of the world (Weeks, 1989, Kranowitz, 1998). When we change processing of information in the brain, this causes an alteration of messages sent by the motor (efferent) nerves so there is an impact on functionality of various parts of the body (Kraus and Anderson, 2017). It also follows that when we alter the way we process sound in the brain, the ear functions differently (Delano and Elgoyhen, 2016).

It is suggested that enhancing ear performance affects the way we process sensory information and can have an impact on tinnitus (Richards, 2003). The ear and brain form a feedback system which can be gradually re-educated through sound. Sensory nerves stimulate and re-map the brain, resulting in improved auditory processing and sound perception. The brain, in turn, sends signals back to the ear to improve its function. These motor signals (originating in a part of the brain stem called the Superior Olivary Nucleus) are part of a continuous feedback loop. Thus the middle ear muscles play an active role in enhancing ear function.

Richards (2003) says:

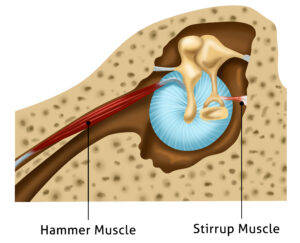

“The efferent nerves run close to, but not within, the same tracts, as the afferent nerves. The Superior Olivary Complex is the region of the brainstem where efferent neurons arise and have their point of origin, but are not within the afferent nuclei. It is this system that is responsible for the auditory reflex activities of the stapedius and the tensor tympanic muscles.” (Figure 2)

This motor activity generates the tone of these muscles, continually monitoring the tension being applied to the ear drum and providing protection to the hair cells from excessive levels of stimuli. It also feeds information back to the hearing organ in the inner ear, causing a mechanical fine-tuning effect on attention and sound localization (Richards, 2003).

The "activated" music of Sound Therapy provides the ear with alternating tones that reactivate and retrain the middle ear muscles. The Sound Therapy system is also designed to stimulate auditory remapping.

Auditory Remapping

Multiple brain regions are involved in tinnitus (Baguley, 2013). Discoveries in recent decades in the field of neural plasticity have demonstrated the potential for brain pathways to be restructured and organised through sensory stimulation (Doidge, 2008; Jenkins, 1990, Sasaki, 1980). Since hearing is one of our primary sensory pathways, this means that using sound may be a key to enhancing nervous system and brain function in a variety of ways. It also opens up a whole new field of potential treatment for ear-related problems (Reavis, 2010).

Since we know that auditory remapping can occur, the question is what kind of stimulus can promote this remapping in such a way as to interrupt and calm the tinnitus signal? Many researchers have looked for this answer, and the work of Tomatis shows some promise in reducing tinnitus (Stillitano, 2014).

Sound, especially classical music, is known to impact several areas of the brain. The use of classical music integrates the proven beneficial effects of music therapy with the neural stimulus of sound therapy (Jausovec, 2003). Classical music, and in particular the compositions of Mozart, have been found to beneficially influence brain function (Jausovec, 2003). It is believed that the rich combination of complex melody, harmony and rhythm inherent in this music is a significant factor in the efficacy of auditory remapping to reduce tinnitus (Joudry, 2009).

A variety of studies have looked at the impact of high frequencies on the auditory system (Tsutomu et al, 2000) conducted a study using psychological measurements of brain responses in which they demonstrated that music containing high frequencies above the audible range had a significant effect on brain activity. In a study using PET to map neural responses, Lockwood et al found that “simple tonal stimuli activate a large and complex network of neural elements” (Lockwood, 1999), that higher frequencies were perceived at more central regions of the brain, as opposed to the surface areas, and that:

“contrary to predictions based on cochlear membrane mechanics, at each intensity, 4.0 kHz were more potent activators of the brain than the 0.5 kHz stimuli.”

Tomatis-based Sound Therapy applies the same principles in an integrated approach. By using classical music with a specific algorithm of augmented high frequencies, Sound Therapy is believed to influence responses in the medial temporal lobe system and bring about adaptations of the central nervous system in order to induce appropriate integration with the limbic system, which is the seat of the brain's emotional responses (Goldstein 2005).

Ear muscle tone and vertigo

One type of tinnitus is the kind that accompanies Meniere’s Vertigo. Dr Tomatis’s writing on Meniere’s syndrome gives a well-informed insight into the possible mechanism of these muscles in effective, overall performance of the ear. Though the role of the middle ear muscles has previously been minimized in hearing research, new evidence now suggests they may play a more active role than previously thought, on both sound sensitivity (Porges, 2014) and vertigo (Tomatis, 1991) (Figure 3).

The integrated approach to healing, represented by the field of integrative medicine, fosters an understanding that each part of a functional system plays a key role in the performance of the whole system (Bland 2015).

Dr. Tomatis writes on Meniere’s:

“To what then is Meniere's vertigo due? I believe I have the authority to declare, as a result of the frequent recoveries we have achieved, that we are dealing with an anomaly in the tension of the stirrup muscle. This muscle, which regulates the pressures of the fluid in the labyrinth, can, like every other muscle, and especially the facial muscles, be suddenly moved by independent, involuntary movements called “twitches.” Each of us has seen or felt one of his own muscles suddenly begin to dance about without his having made any voluntary movement to cause this. Such a twitch often happens on the face, and when one questions those suffering from Meniere's vertigo, one often discovers its coexistence with a facial twitch. In fact, the distribution of the nerves in the facial muscles is similar to that which governs the stirrup muscle. Consequently, under the impetus of the stirrup plate, which drives itself into the labyrinth like a piston, the endolymphatic liquid is going to be stirred up into a storm, so bringing in its wake a cataclysmic depression.

"In order to stop such a tempest, everything is put in place to relax this muscle, which is altogether too active. Hence vertigo arises, under the agitated movement of the endolymphatic liquid, and so do buzzings (perceived as bodily noises, following the non-regulation of inhibitory phenomena) and hearing loss, as a result of the reduced tonus of the stirrup muscle."

"Once vertigo sets in, the musculature no longer is able to easily ensure its normal functioning, and internal irritation triggers off discharge which in turn brings about hypertension. Through the use of the Electronic Ear and its electronic gating mechanisms, the hypertension of the stirrup muscle may be reduced, thereby allowing it to resume its proper balancing role. This is followed by diminution of the buzzing noises in the majority of cases and finally the restoration of hearing to some degree.” (Tomatis, 1991)

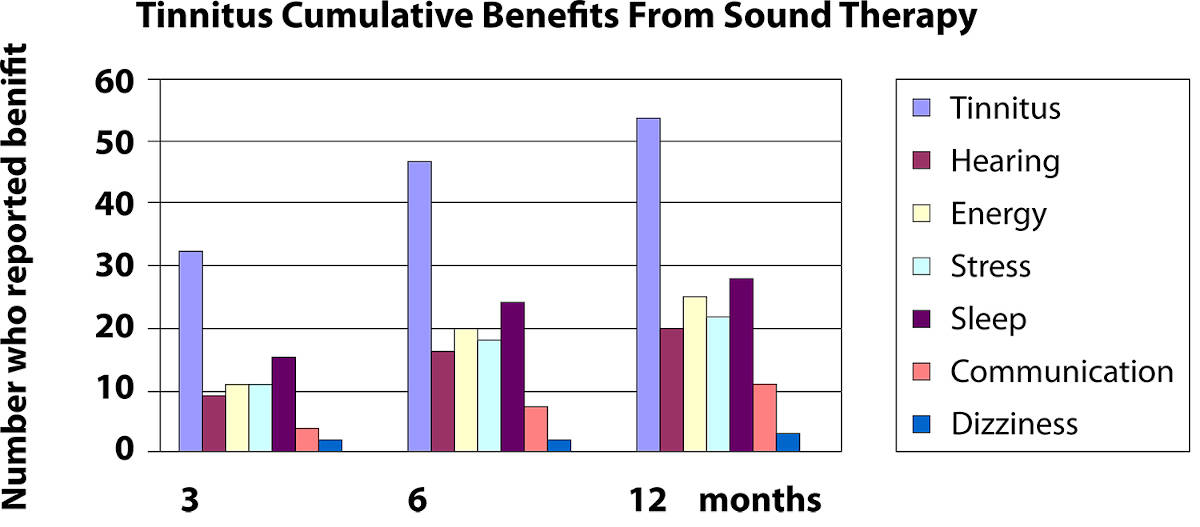

Tinnitus reduction through Sound Therapy

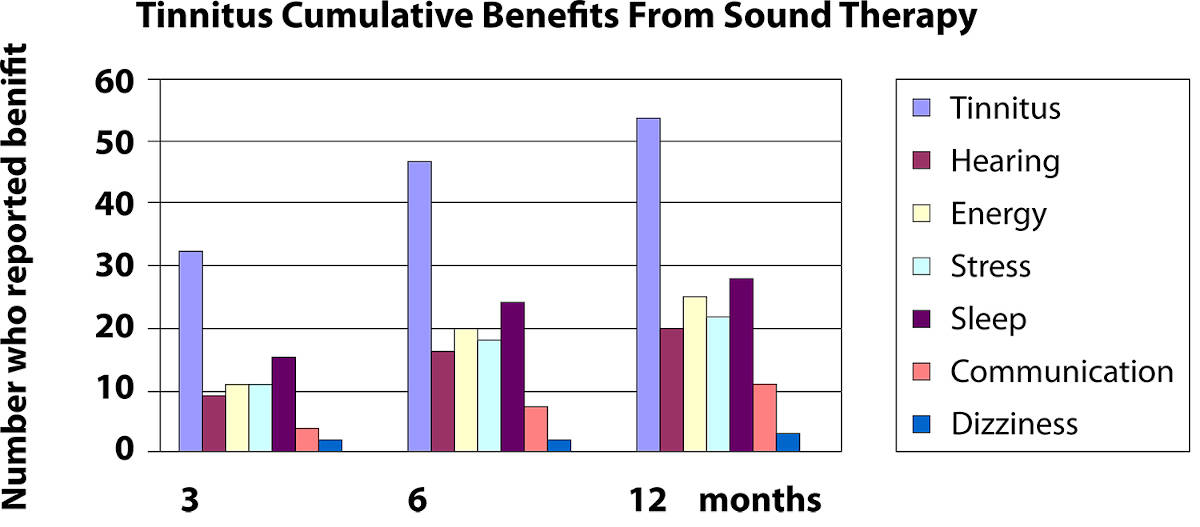

Some Sound Therapy listeners have experienced both improved hearing and reduced tinnitus, even when caused by noise induced trauma (Joudry 2009). This is because an integrative approach, based on stimulating the whole system of the body to heal itself, results in improved health of an entire functional system, and therefore often results in improvement to numerous symptoms, or illnesses, of that system (Bland 2015). While this is by no means a guaranteed result, it has been shown that improvement is possible, so the diagnosis that all tinnitus sufferers must simply learn to live with their condition no longer seems appropriate.

Conclusion

Dr Tomatis’s theory that Meniere’s and some forms of tinnitus are related to anomalies in function of the stirrup muscle shows promise in explaining why several of the symptoms of these conditions are alleviated by restoring normal tone to the middle ear muscles. Tomatis was a pioneer in thinking about a whole systems approach to medicine, and his understanding of the ear is proving to hold considerable value as we continue to unravel its mysteries.

We know that classical music alone causes a response in at least ten different brain centres. In addition, understanding of brain plasticity that has been developed in recent decades explains the possibility of neural and auditory remapping, and why activation of many different brain centres with complex, filtered classical music is often effective in relieving tinnitus. Finally, thousands of successful cases of alleviation or recovery from tinnitus indicate positive results for the application of the Sound Therapy system for tinnitus and tinnitus-related conditions over a longer listening duration.

REFERENCES

- Australian Hearing’s Health Report: Is Australia Listening? Attitudes to hearing loss. (2008). pg10-13.

- Axelsson, A. and Prasher, D., (2010) Tinnitus induced by occupational and leisure noise, Noise Health 2000; 2:47-54

- Baguley, D. (2013). Tinnitus, The Lancet, VOLUME 382, ISSUE 9904, P1600-1607, NOVEMBER 09, 2013.

- Bland J. (2015). Functional Medicine: An Operating System for Integrative Medicine. Integrative medicine (Encinitas, Calif.), 14(5), 18–20. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4712869/

- Delano P. H., Elgoyhen, A. B. (2016) Editorial: Auditory Efferent System: New Insights from Cortex to Cochlea, Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, Vol 10, https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fnsys.2016.00050

- Doidge, N. (2008). The Brain the Changes Itself. Scribe Publications, Carlton North, Vic.

- Engineer, N., Riley, J., Seale, J. et al. (2011). Reversing pathological neural activity using targeted plasticity. Nature470, 101–104 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09656

- Fausti, S., et al., (2005). “Hearing Health and Care: The Need for Improved Hearing Loss Prevention and Hearing Conservation Practices.” Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development, 42(4), 45-62.

- Goldstein, B. A. et al, (2005). “Tinnitus Improvement with Ultra-High-Frequency Vibration Therapy.” International Tinnitus Journal, 11, No. 1, 14–22.

- Holmes S, Padgham ND. (2009), Review paper: more than ringing in the ears: a review of tinnitus and its psychosocial impact. J Clin Nurs. 2009 Nov;18(21):2927-37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02909.x. Epub 2009 Sep 4. PMID: 19735344.

- House JW, Brackmann DE. (1981). Tinnitus: surgical treatment. Ciba Found Symp. 1981;85:204-16. doi: 10.1002/9780470720677.ch12. PMID: 6915835.

- Jastreboff, P.J., Hazel, W.P., (1993). “A Neuro- physiological approach to Tinnitus: Clinical Implications,” British Journal of Audiology, 27, 7-17.

- Jausovec, N, and Habe, K., (2003). “The “Mozart Effect”: An Electroencephalographic Analysis Employing the Methods of Induced Event-Related Desynchronization/ Synchronization and Event Related Coherence,” Brain Topography. 16(2):73-84, 24.

- Jenkins, W. M., et al, (1990). “Functional reorganization of primary somatosensory cortex in adult owl monkeys after behaviorally controlled tactile stimulation,” J Neurophysiol 63: 82-104, 0022-3077/90.

- Joudry, P. and Joudry, R., (2009). Sound Therapy: Music to Recharge Your Brain, Sound Therapy International, NSW, Australia.

- Joudry, R. (2021), Why classical music can provide relief for tinnitus, https://prwire.com.au/pr/53634/why-classical-music-can-provide-relief-for-tinnitus

- Kranowitz, Carol Stock, (1998). ‘The Out of Synch Child.’ New York: Penguin.

- Kraus, N. and Anderson, S. (2017). The ear-brain connection: the role of cognition in neural speech processing, ENT & Audiology News. 26 June 2017.

- Leaver AM, Renier L, Chevillet MA, Morgan S, Kim HJ, Rauschecker JP. Dysregulation of limbic and auditory networks in tinnitus. 2011 Jan 13;69(1):33-43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.002. PMID: 21220097; PMCID: PMC3092532.

- Lockwood, A.H., et al, (1999). “The Functional Anatomy Of The Normal Human Auditory System: Responses To 0.5 And 4.0 Khz Tones At Varied Intensities.” Cerebral Cortex, 9, 65-76.

- Porges, S. W., (2014). Reducing Auditory Hypersensitivities in Autistic Spectrum Disorder: Preliminary Findings Evaluating the Listening Project Protocol, Frontiers in Pediatrics, 1;2:80. doi: 10.3389/fped.2014.00080. PMID: 25136545; PMCID: PMC4117928.

- Rauschecker, J. P., (2010). Tuning Out the Noise: Limbic-Auditory Interactions in Tinnitus, Neuron, 66, June 24, 2010.

- Rauschecker, J. P., May, E., Madoux, A. and Ploner, M., (2015) Frontostriatal Gating of Tinnitus and Chronic Pain, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Vol 19, Issue 10, P 567-578.

- Reavis, Kelly M.; Chang, Janice E.; Zeng, (2010). Fan-Gang Patterned sound therapy for the treatment of tinnitus, The Hearing Journal: November 2010 - Volume 63 - Issue 11 - p 21-22,24 doi: 10.1097/01.HJ.0000390817.79500.ed

- Richards, G., (2003). “Auditory Neurology that May Support the Tomatis Theory and other Auditory Intervention Techniques.” Presented to Australian Audiological Society Conference Brisbane. Ciited on 22nd July 2021 on https://mysoundtherapy.com/au/wp-content/uploads/rp-auditory-neurology-that-may-support-the-tomatis-theory-and-other-auditory-intervention-techniques-1.pdf

- Sasaki et al., (1980). Gerken et al, 1986: Salvi et al., 1992. Cited in Jastreboff, P.J.& Hazel, W.P. 1993, “A Neurophysiological approach to Tinnitus: Clinical Implications,” British Journal of Audiology, 27, 7-17.

- Stillitano, C., Fioretti, A., Cantagallo, M., Eibenstein, A., (2014). The Effects of the Tomatis Method on Tinnitus, International Journal of Research in Medical and Health Sciences, 4, No.2.

- Thompson, Tres., (2011). UT Dallas Research Studies How Brain Plasticity Can Affect Tinnitus, The Hearing Review, Cited on 16th July 2021 on https://www.hearingreview.com/hearing-loss/tinnitus/ut-dallas-research-studies-how-brain-plasticity-can-affect-tinnitus

- Tomatis, A. A., (1991) The Conscious Ear, Station Hill Press, 1991.

- Tsutomu, O. et al, (2000)., “Inaudible High Frequency Sounds Affect Brain Activity: Hypersonic Effect,” J Neurophysiol 83:3548-3558.

- Weeks, Bradford S., (1989). “The Therapeutic Effect of High Frequency Audition and its Role in Sacred Music”;in About the Tomatis Method, Gilmor, T M., et al. The Listening Centre Press, Toronto. Cited on http://weeksmd.com/?p=714

Start Getting Relief Today

Click here to choose your package