Blog

Rehabilitating the Nervous System with Sound Therapy

Our nervous system is essential to our well being, just like air and water. It’s an invisible superhighway that links all functions in our body. Its functioning is fundamental to how we feel, how we maintain our energy levels, how we show up and perform in life.

The problem so many of us are facing today is that our current lifestyle presents continuous and unrelenting stress demands, which our nervous system was not designed to accommodate. Our body gets stuck in the “on” fight or flight position. We don’t know how to release the tension and come down from the adrenaline surge.

In our evolution, threatening situations were short lived. Our fight or flight mechanism kicked in if we were being chased by a lion, and afterwards we went back to a state of peace, so we could rest and regenerate.

In today’s world, we have continual deadlines to meet, bills to pay, traffic to negotiate, corporate ladders to climb…so many of us develop the habit of staying in the switched-on stress response state continually. After some years of this behaviour, our adrenals wear out. We are then in a state of adrenal fatigue or burn out, in which the health of our whole body is affected. Chronic stress and burn out has been linked to digestive issues, skin problems, high blood pressure, sleep disorders and auto-immune diseases (Smerling, 2018) including MS and Parkinsons (Chan et al 2017).

However, it has been shown that if a stress condition is treated, it reduces the likelihood that a more serious auto-immune disease will develop (Wurtman, 2018).

Treatment is commonly done with anti-depressants, but an option for those who choose a wholistic health approach, that is more comprehensive and without negative side effects, is to use retraining techniques. These include bio-feedback and various conscious retraining methods, including chi kung, tai chi, Feldenkrais or Alexander Technique.

What are the approaches to recovery?

The tendency to store stress in the body is operating at the unconscious level of the brainstem, but it can be controlled by the higher brain centres, if we learn how.

This work is of particular interest in dealing with trauma. Trauma is the sensations left in the body which we keep revisiting or replaying after an event in the past which was threatening to our safety (Chitty, 2018).

Various techniques have been tried to unravel and release these traumatic replay patterns. One is mindfulness or meditation, but this can be re-traumatising as it creates a lot of stillness and openness in which the traumatic feelings may be reactivated and become more dominant. What is necessary to change the body’s habitual response and stop this replaying of the traumatic sensations is a retraining process to learn self-regulation. This can be done with neuro-feedback or various somato-sensory or emotional release methods.

Another technique which can support such change in a very easy to apply and non-threatening way is Sound Therapy. Using beautiful music that is filtered to provide a very precise re-education of neural pathways, it re-maps patterns within the nervous system and rebuilds and strengthens self-regulation skills, reinforcing the dominance of the newest, social engagement branch of the vagal nervous system.

The encouraging reality is that you have the capacity to heal yourself, if you can get the right stimulation into your nervous system. What you need is to learn, at a very subtle level, a new set of behaviour responses to replace the old, reactive programming that was put in place years ago and is no longer serving you.

Recovery is about learning to become a better listener to the lower brain and its automatic reactions, so that we can process and release stress after the event. In this way it doesn’t get stored and built up in your system and become toxic and debilitating.

However, this type of retraining is difficult. It requires time and dedication to learn to recondition our nervous system using these conscious retraining techniques. It requires hours of study, supported by qualified coaching, and can be costly.

This is where we see the benefit of using a technique like Sound Therapy, which is a passive process, requiring minimal effort or time, and which can reinforce and facilitate the success of such conscious retraining methods. Sound Therapy, as developed by the ear specialist, Dr Alfred Tomatis, uses filtered and activated music to recondition the auditory pathways. Research by Stephen Porges, the developer of the Polyvagal theory, and numerous others, has proven that Sound Therapy can significantly enhance our ability to switch our nervous system into the calming and beneficial social engagement pathways, which is possible only when our autonomic stress levels have been switched off in favour of the newer, myelinated, social engagement branch of the vagus nerve (Gerritsen, 2009; Porges et al, 2015).

Available in its portable form, Sound Therapy has the great advantages of being pleasant, easy, unobtrusive and requiring no additional time to be set aside. It can be done in concert with daily activities, or indeed with retraining and neural regeneration activities (Joudry, 2015).

It is common for people healing from adrenal fatigue and other stress related conditions to slow down for a short time, take on some retraining activities, get a little bit of recovery, and then go back into the fray, possibly losing the gains they may have achieved. Sound Therapy has the advantage that it can be used continually both when on retreat and in action, so it provides continuous support during various phases of the healing journey.

Polyvagal theory and Sound Therapy

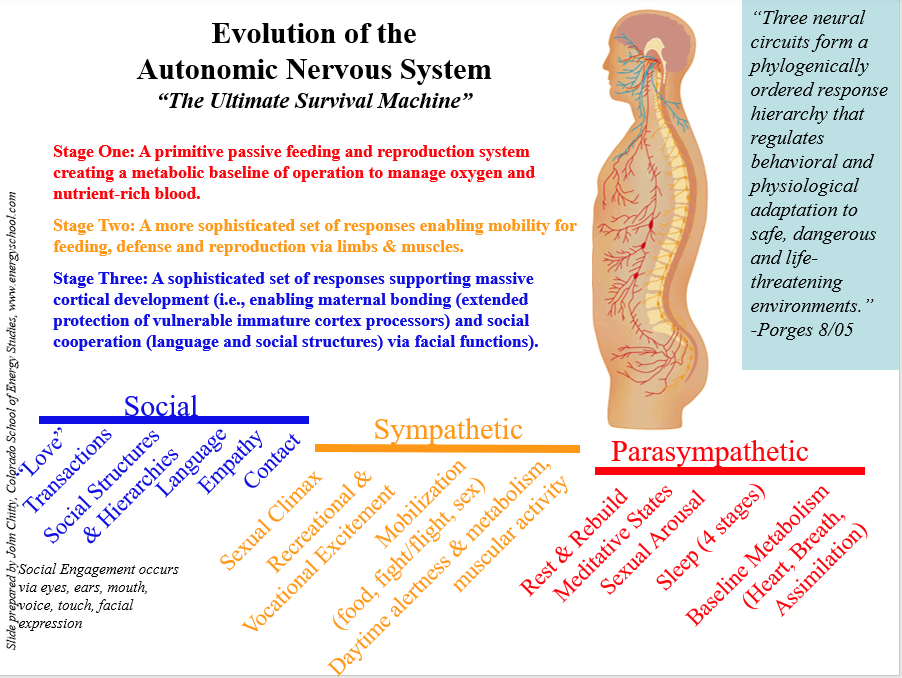

For some decades we have been aware of two different systems within the Autonomic Nervous System. These are the Sympathetic, known for its mobilisation and fight or flight reaction, and the older, Parasympathetic, which causes an organism to freeze in immobility, or to rest and digest.

Stephen Porges in his Polyvagal Theory has proposed a third system, the Social Engagement system, which is much newer in evolutionary terms.

This system is unique to mammals, and much more developed in primates and humans. It is fundamental to maternal bonding, and all other social relations which stem from that primal first connection (Chitty, 2018).

Great interest has been activated in the therapeutic community by the new understanding of our vagal systems. Recent studies reveal its key role in inflammation, mood and pain regulation. (Yuan and Silberstein, 2016)

Knowledge of the role of the vagal nerve goes back as far as Darwin.

“The heart, guts and brain communicate intimately via a nerve – the pneumogastric nerve (or vagus) – the critical nerve in the expression and management of emotions in both humans and animals. When the mind is strongly excited it instantly affects the state of the viscera.” Charles Darwin

Various therapeutic methods are being explored to assist people in accessing and turning on the pro-social mammalian system. You could say that we are learning to react like mammals, not reptiles!

This work is paralleled by Tomatis’s discoveries about our bonding to the mother (and later to others) through sound (Tomatis, 1991).

When we are able to operate from the more evolved, social engagement system, life is very different. We are calm, present, in our own agency, able to respond and engage with others in a warm compassionate way. We can ‘be’ and express ourselves in a soft, responsive, alert and confident manner, and engage with true empathy (Chitty, 2018).

What we learned from Polyvagal Theory

“The Polyvagal Theory provided us with a more sophisticated understanding of the biology of safety and danger, one based on the subtle interplay between the visceral experiences of our own bodies and the voices and faces of the people around us. It explained why a kind face or a soothing tone of voice can dramatically alter the way we feel. It clarified why knowing that we are seen and heard by the important people in our lives can make us feel calm and safe, and why being ignored or dismissed can precipitate rage reactions or mental collapse. It helped us understand why focused attunement with another person can shift us out of disorganized and fearful states. In short, Porges’s theory made us look beyond the effects of fight or flight and put social relationships front and center in our understanding of trauma. It also suggested new approaches to healing that focus on strengthening the body’s system for regulating arousal.”(Van Der Kolk, 2014)

How the nervous system works

Our Autonomic Nervous System fires muscular tension impulses, triggered by feedback signals from the internal and external worlds, at millisecond intervals below conscious awareness. These muscle impulses fire our thoughts.

When we become triggered into a fear or stress reaction, the older system takes over. We react unconsciously, automatically, either aggressively or passively, but without the kind of subtle, embodied awareness that is necessary for real communication.

| Social Engagement System | SNS Sympathetic Nervous System | PNS Parasympathetic Nervous System |

| Tend and befriend | Intense rapid response | Rest and digest |

| Engage | Fight or Flight | Freeze |

| Prosociality and compassion | Defensive protective reactions | Calm and meditative states |

With the help of various retraining methods, we are discovering that instead of being triggered into fight, flight or freeze, we are learning to access those more compassionate, conscious, trusting, loving responses to others—things that are only available to us when we feel safe.

The social engagement system must dominate for our self-regulation to work well. It’s not a matter of balance but of executive organisation (Chitty, 2018).

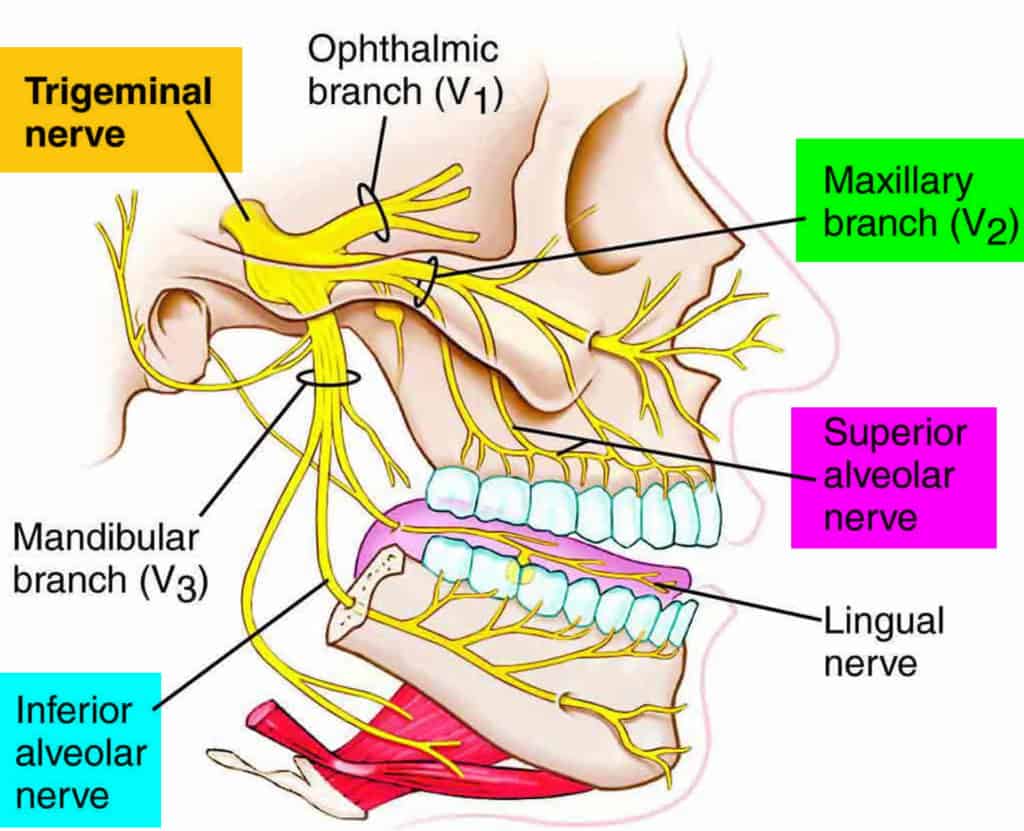

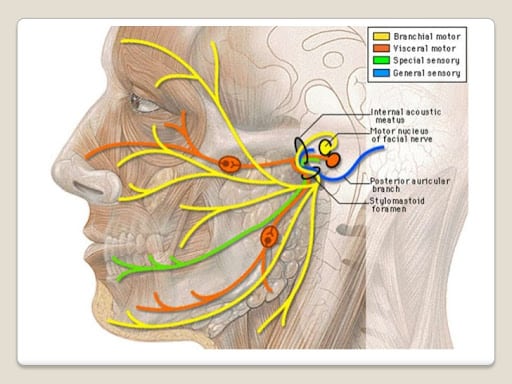

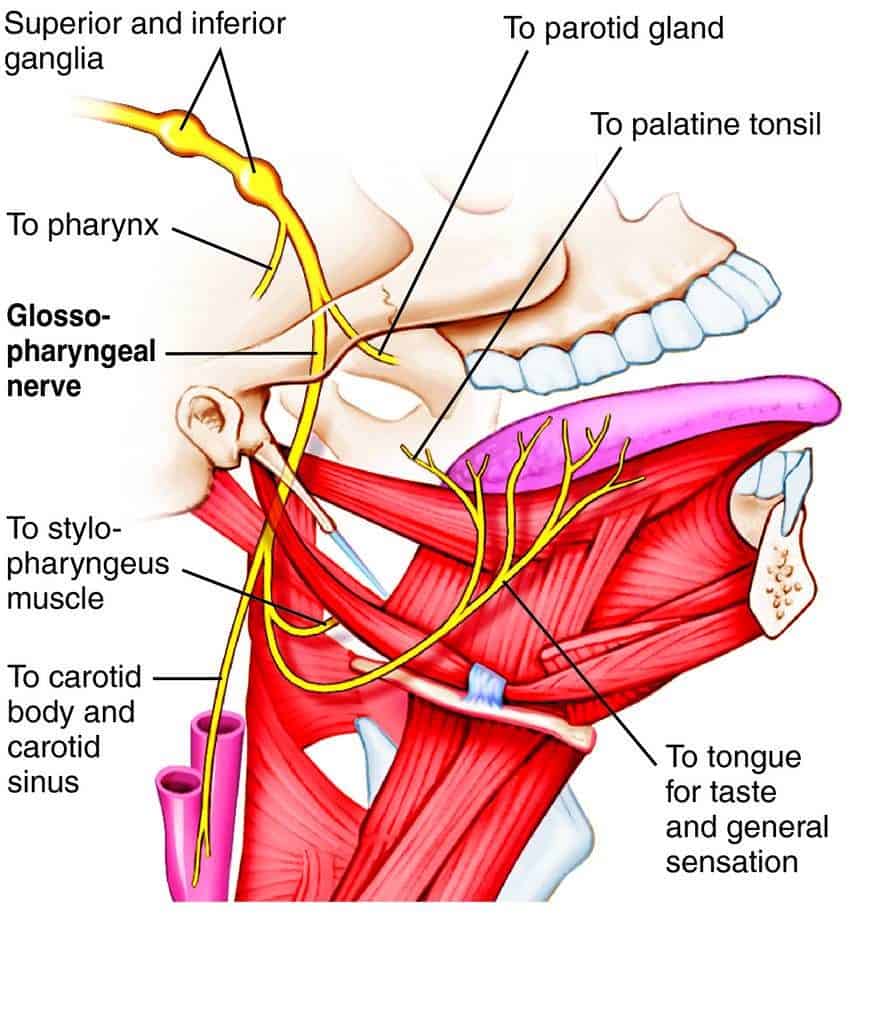

There is a particular physiological link between Tomatis’s work and Porges’ work, and this involves the cranial nerves. The vagal nerve works in concert with several other cranial nerves in activating these systems.

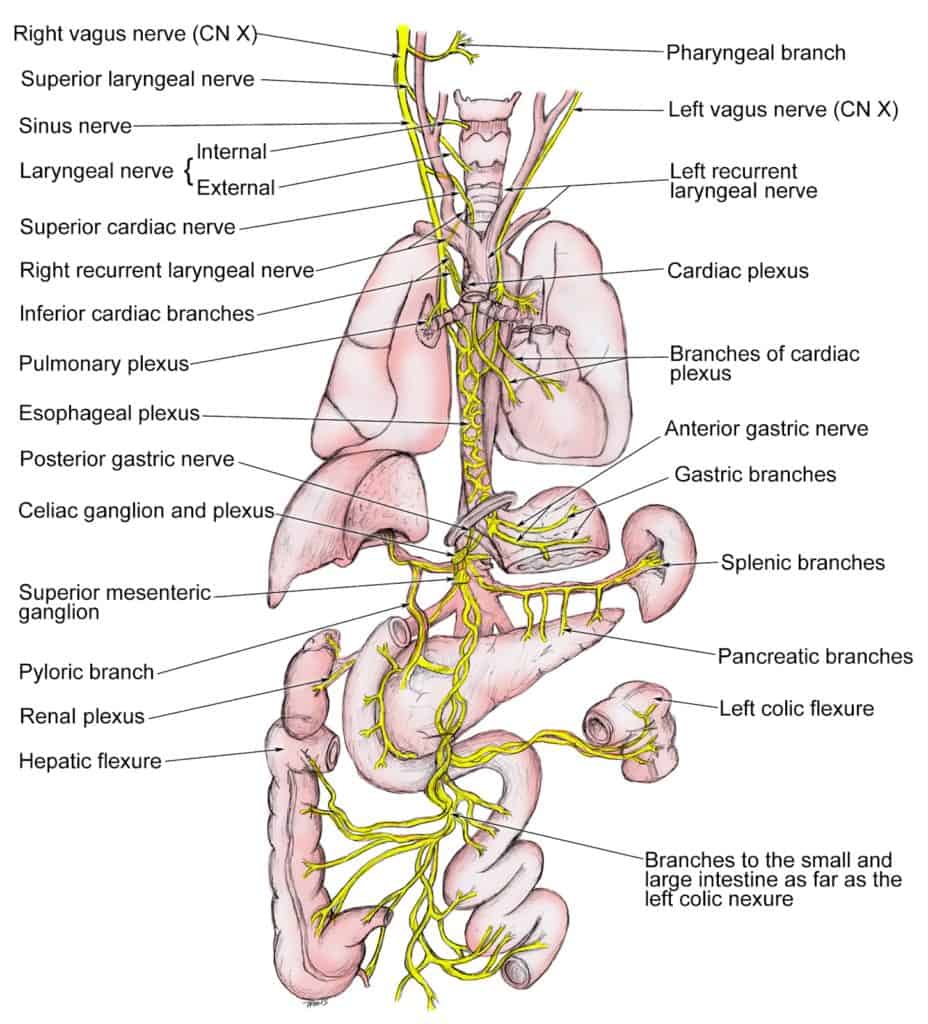

Vagal nerve

Parasympathetic control of the heart, lungs and digestive tract.

The vagal nerve innervates all our internal organs with the exception of the adrenal glands.

Trigeminal nerve

Sensing facial expression, mouth and tongue, chewing and swallowing

Facial expression, mainly in upper face, tear production, saliva, taste. Regulates middle ear muscles.

Tongue, sensations and taste. Speech.

How to bring about change

As well as conscious thought, breathing and other subtle physiological processes, stimulation of the middle ear muscles has been found to significantly affect our vagal function.

Sound Therapy was first discovered by Tomatis in the 1950s, and much work was done on our understanding of listening as an active process to assist in learning and vocal production.

More recently, research has shown its impact on many conditions including auditory processing, sound differentiation in noise, anxiety and stress responses, developmental delay, epilepsy, tinnitus and recovery from stroke, brain damage and neural degeneration (Gerritsen, 2009).

Porges work has revealed the evolutionary and neurophysiological basis for what has already been demonstrated by Tomatis.

How the Sound Therapy mechanisms work.

Dr Tomatis put forward a unique theory that listening to Sound Therapy, which uses music that has been processed and activated using his Electronic Ear, provides a stimulus which exercises and normalises the middle ear muscle function. This then opens the whole auditory pathway to rehabilitation through sound. The complex harmonies and melodies of this uniquely filtered sound go on to rewire and restore functionality to large portions of the nervous system, via the cranial nerves which have many linkages to our auditory function.

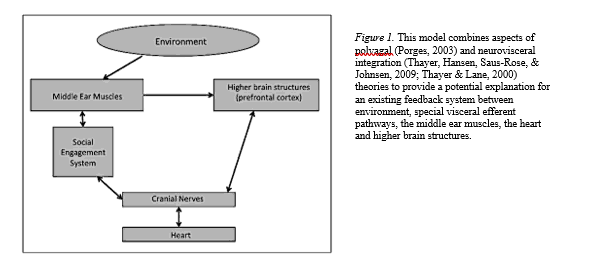

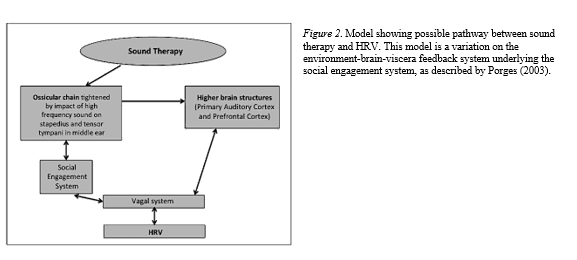

A pilot study using Joudry’s portable Sound Therapy program was undertaken by Warhurst and Kemp at Sydney University. Porges has demonstrated that activating the middle ear muscles tunes us into the voice, by dampening low frequency background noise and enabling us to focus more on the high frequencies in the human voice. “When the birds are singing we feel safe” (Porges,2009).

“Middle Ear Muscles have sensory endings, which – through neural arches originating from the anterior horns of the spinal cord – regulate levels of contraction, establishing bio-feedback. Recent findings have thus redefined conceptualisations of Middle Ear Muscle movement, in particular their movement in response to different sound frequencies” (Warhurst, 2012).

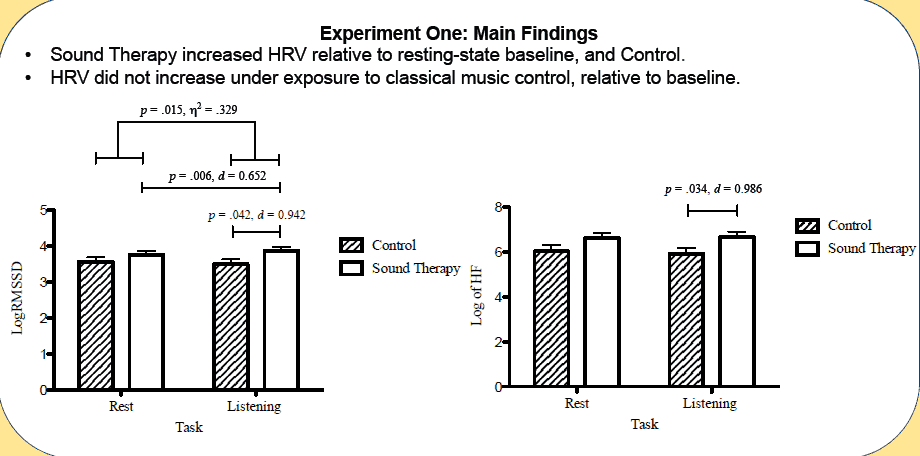

Warhurst and Kemp used Heart Rate Variability (HRV), which is an established measure for good vagal regulation, to test the impact of Sound Therapy on normally functioning university students. They found that listening to Sound Therapy for a short period of time significantly increased heart rate variability compared to the control group (Warhurst & Kemp, 2012).

(Porges,2003)

and neurovisceralintegration

(Thayer,Hansen, Saus-Rose, & Johnsen, 2009; Thayer & Lane, 2000)

theories toprovide a potential explanation for an existing feedback system betweenenvironment, special visceral efferent pathways, the middle ear muscles, the heart and higher brain structures.

Porges(2003)

.

Warhurst concluded that participants who were exposed to Sound Therapy showed improvements on well-established measures of vagal regulation, over and above participants who were exposed to a classical music control. This supports the notion that exposure to Sound Therapy causes increases in HRV. This gives insight into the link between the middle ear muscles, the cranial nerves and the heart (Warhurst & Kemp, 2012).

In conclusion

To improve our self-regulation and regain a balanced and well organised nervous system, we need to restore the correct hierarchy in our vagal neural branches. The most recently evolved, higher order, social engagement branch of the vagal nerve needs to be the primary operating system.

Mindfulness doesn’t necessarily work for people who are traumatised, as it can create an empty space in which the trauma replays itself.

Neural feedback can be a useful tool as it teaches self-regulation. Various techniques are available for retraining the nervous system which can be very beneficial. However, such processes are time consuming and require dedication and qualified instruction.

Sound Therapy has proven to be an effective tool for helping to improve self-regulation and thus make social engagement more possible. It works directly on the autonomic nervous system, has been proven to enhance the function on the cranial nerves, the middle ear muscles and to promote stress relief and better self-regulation and social engagement. Therefore, it is an important tool to be considered as a support to any system for retraining our nervous system.

References

Chan, E., Yee-Lam, Bai, Ya, Hsu, Ju-Wei, Huang,Kai-Lin, Su, Tung-Ping, Li, Cheng-Ta, Lin, Wei-Chen, Pan, Tai-Long, Chen,Yu-Chun, Tsai, Shih-Jen, Chen, Mu-Hong, (2017). Post-traumatic Stress Disorderand Risk of Parkinson Disease: A Nationwide Longitudinal Study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 25. 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.03.012. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28416268 Citedon 13/12/18

Chitty, J. (2018). The Triune Autonomic Nervous System Presentation, http://energyschool.com/resources/polyvagal-theory/

Gerritsen, J. (2009). A Review of Research done on TomatisAuditory Stimulation, http://www.sacarin.com/code/Review%20of%20Tomatis%20Research.pdf

Joudry, P. and Joudry, R. (2015). Sound Therapy: Music to Recharge Your Brain, Sound Therapy International, Australia.

Kemp, A. H., Qintana, D.S., Felmingham, K. L., Matthews, S.,& Jelinek, H. F. (2012). Depression, comorbid anxiety disorders, and heartrate variability in physically healthy, unmedicated patients: implications for cardiovascular risk. Plos One, 7(2), e30777. Doi: 10.137/journal.pone.0030777

Porges, S. W., & Lewis, G. F.(2010). The polyvagal hypothesis: common mechanisms mediating autonomic regulation,vocalizations and listening Handbook of Behavioral Neuroscience (Vol. 19, pp. 255-264).

Porges, S. W., Bashenova, o., Bal, E., Carlson, N., Sorokin, Y.,Heilman, K. J., Cook, E., and Lewis, G. F. (2014). Reducing Auditory Hypersensitivities in Autistic Spectrum Disorder: Preliminary Findings Evaluating the Listening Project Protocol, Frontiers in Pediatrics, 2014; 2: 80. Published online 2014 Aug1. doi: [10.3389/fped.2014.00080]

Porges, S. (2009). The polyvagal hypothesis: common mechanisms mediating autonomic regulation, vocalizations and listening. In: Stefan M. Brudzynski, editors, Handbook of Mammalian Vocalization. Oxford: Academic Press, 2009, pp 252-264 ISBN: 978-0-12-374593-4.

Porges, S. (2011). The polyvagal theory: neuropsychological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication and self-regulation, W. W. Norton and Company, New York.

Smerling, H. (2018). Autoimmune disease and stress: Is there a link? Harvard Health Publishing https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/autoimmune-disease-and-stress-is-there-a-link-2018071114230

Thayer, J. F., Hansen, A. L.,Saus-Rose, E., & Johnsen, B. H. (2009). Heart rate variability, prefrontal neuralfunction, and cognitive performance: the neurovisceral integration perspective on self-regulation, adaptation, and health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 37(2), 141-153. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9101-z

Tomatis, A. A. (1991). The Conscious Ear: My Life of Transformation Through Listening, Station Hill Press.

Van Der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York: Viking Penguin. p. 81. ISBN 9780670785933. Retrieved 3February 2018.

Wurtman, J. (2018). Will Stress Lead to Autoimmune Disease? Psychology Today, https://www.psychologytoday.com/au/blog/the-antidepressant-diet/201806/will-stress-lead-autoimmune-disease

Warhurst, L. & Kemp, A. (29 November, 2012) Listen to your heart: A preliminary investigation of the influence of sound therapy on heart rate variability. Poster presented at the 22nd Australasian Psychophysiology Conference, University of New South Wales, Sydney.

Warhurst, L. (2012). Listen to Your Heart: A PreliminaryInvestigation of the Influence of Sound Therapy on Heart Rate Variability, Honours Thesis, Psychology Dept, Sydney University.

Yuan, H & Silberstein, S.D. (2016). Vagus Nerve and Vagus Nerve Stimulation, a Comprehensive Review: Part II. Headache. 56. 259-266.10.1111/head.12650.

Tags: HRV, polyvagal theory, self regulation, social engagement, Sound Therapy, vagal, vagus

“The greatest journey in my life had been to help many thousans of people to improve their ear and brain health through the use of Sound Therapy”

Rafaele Joudry

Founder and Author

Categories

- A better way to support independent living

- Audio

- Audiology

- Auditory deprivation

- Auditory Processing

- autism

- BBE Process

- Brain

- Brain Optimisation

- Breathing

- Charities we support

- Chemical Toxins

- children

- Choosing the Music

- Classic Music

- Colds and infections

- conductor

- Depression

- Digital Compression

- Dizziness

- Dystonia

- ear infections

- Ear muscles

- Ear Research

- Emotional Wellbeing

- General

- gut brain connection

- Hearing

- i-pod hearing damage

- Indigenous Literacy Day

- Koorie Story telling

- learning difficulties

- Literacy

- Memory

- Meniere's

- musical talent

- Nervous System

- Neuroscience

- Noise

- Nutritional Supplements

- Pauline McLeod

- Preventing Sudden Deafness

- Read and Exceed

- Reducing Noise exposure in Australia

- Research

- Sound Therapy

- Stress

- Supplements or drugs

- The Music

- Tinnitus

- Tinnitus Treatment

- Tomatis

- travel

- vaccination

- vertigo

- Videos